Community Embraces New Word Game at Mid-Year Play Day This past Sunday, families at Takoma Park’s Seventh Annual Mid-Year Play Day had the opportunity to experience OtherWordly for the first time. Our educational language game drew curious children and parents to our table throughout the afternoon. Words in Space Several children gathered around our iPads […]

Read moreWord games have been stuck on spelling for a century. Crosswords went viral in the 1920s. Scrabble followed. The $2.4 billion mobile word game market is dominated by anagrams, letter tiles, and vocabulary trivia. What a word means—and how it connects to other words—is usually beside the point.

We think there’s another way. Our games operate at the level of meaning. They ask players to navigate semantic space, not rearrange letters. This changes everything: how difficulty works, who can win, and what can go wrong.

A million ways to win

Most word puzzles have one right answer. You either know it or you don’t. This creates a natural ceiling: games optimize for their core audience, and everyone else feels excluded.

Our puzzles have countless valid solutions. In Other Words offers roughly a million paths to victory on any given day. Only 10-15 of those paths are three-hop “Genius” solutions, but players don’t need genius to win. They need their own vocabulary, their own associations, their own mental map of how language works.

A nine-year-old and a grandparent solve the same puzzle differently. Someone who knows 1980s hair bands navigates differently than someone who knows 2010s K-pop. The puzzle accommodates them both.

Other word games ask: can you guess our answer? We ask: can you find your own way through language?

The crossword problem

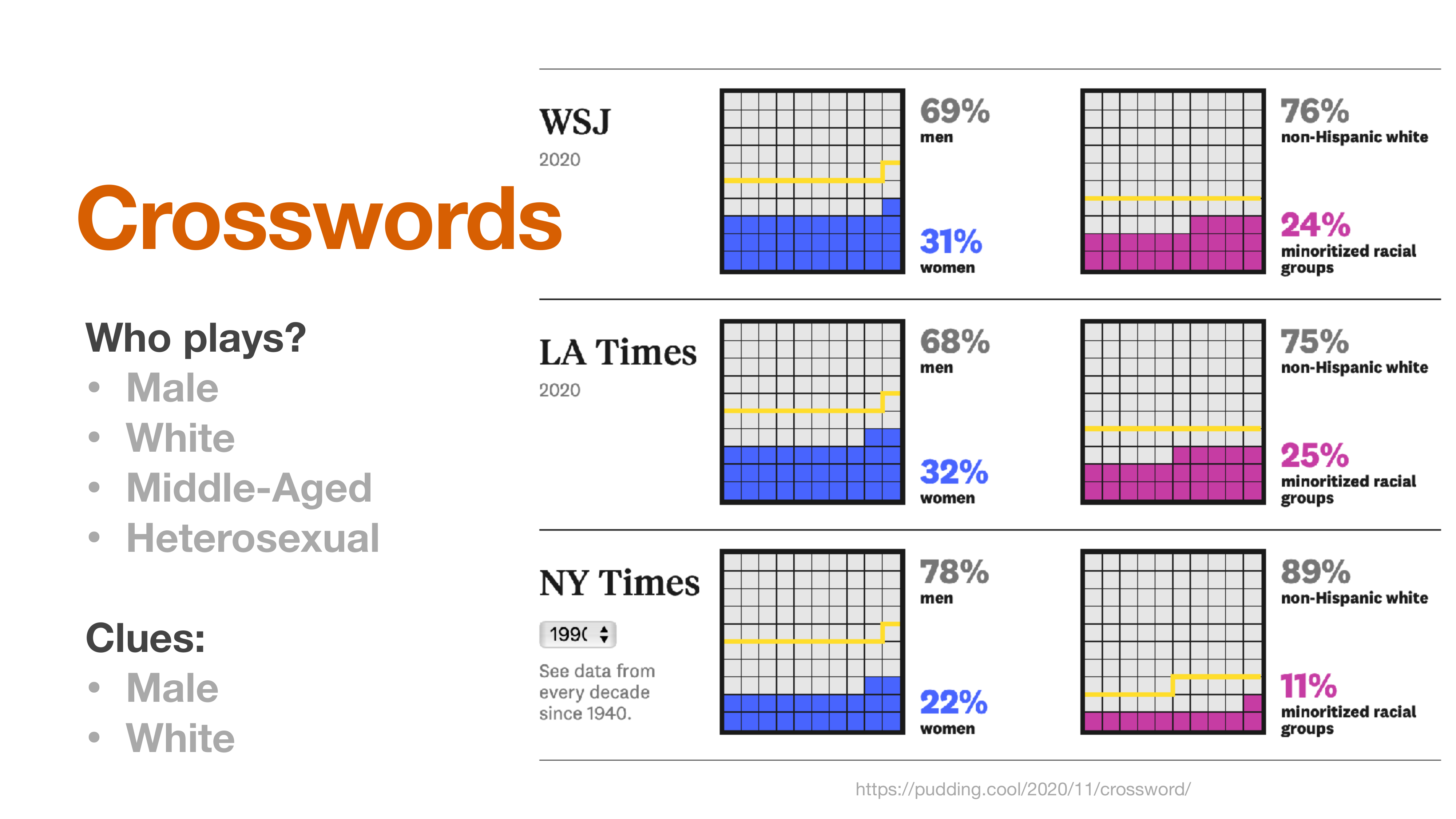

Single-answer word games have a demographic problem. The Pudding’s analysis of crossword puzzles found that clue writers skew male, white, middle-aged, heterosexual. The puzzles reflect their creators. Players who share that background feel at home. Everyone else encounters unfamiliar references and feels like the puzzle wasn’t made for them.

When your game has a million solutions, this pressure eases. Players don’t need to know all the hard words—just enough words to find their own path. Cultural references that would be gatekeeping in a crossword become optional routes in our games. You can win whether your breakfast is Cheerios, Vegemite, chapatti, or congee.

puzzle

Cultural

Generational

Geographic

Socioeconomic

Linguistic

Disability

Gender

Racial/ethnic

Every word in context

Meaning-based games introduce a problem that spelling games never faced: unintended offense. When words appear together in semantic clusters, their relationships carry implications. We’ve learned this the hard way.

Fantastical Figures

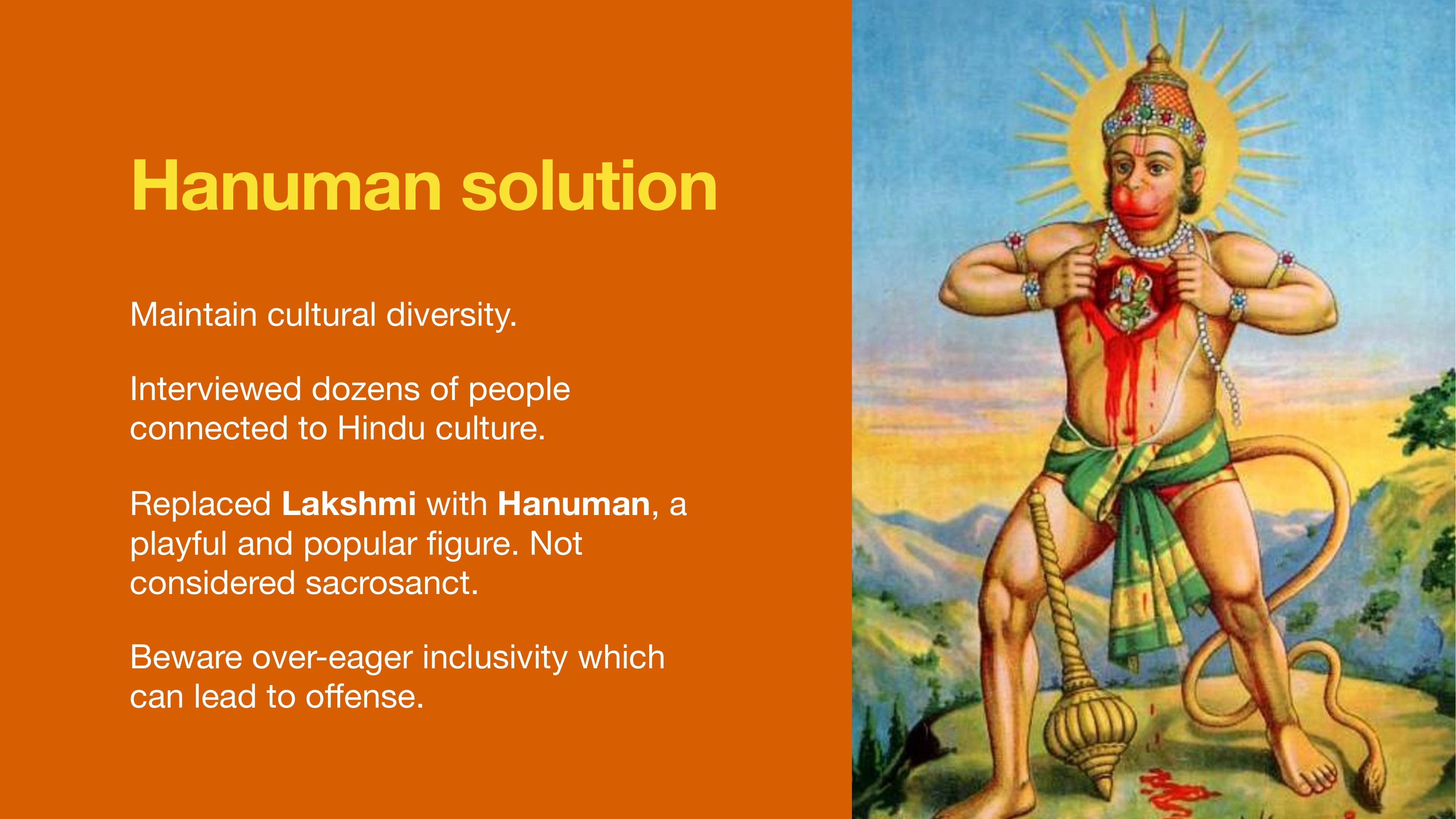

An early word cloud grouped mythological beings: Anansi, Dracula, Medusa, Thor, Sun Wukong—and the Hindu goddess Lakshmi.

The problem: Lakshmi is a revered deity for hundreds of millions of people. Placing her alongside Dracula treats a sacred figure as fantasy entertainment. Would you pair Jesus with Dracula?

We interviewed dozens of people connected to Hindu culture. The solution was Hanuman—a beloved figure, playful and popular, but not sacrosanct in the same way. Over-eager inclusivity had almost led to offense.

Guilty Pleasures

A category called “Guilty Pleasures” included manicures, pedicures, chick flicks, and gossip magazines. The gendered assumptions were baked in. Are guys who go fishing having a guilty pleasure?

We renamed it “Treat Yourself” and rebuilt the cluster: chocolate, napping, fresh flowers, bubble baths. The concept survived; the stereotype didn’t.

Breakfast

An early breakfast cluster: eggs, bacon, McMuffin, sausage, cornflakes, pancakes. Edible, but culturally narrow.

We had two options: expand to include dim sum, miso soup, chapatti, and congee—or cut a different slice entirely, like “Pastries of the World.” Both work. The original didn’t.

Some problems are subtler. “Black” as a color can co-occur awkwardly with race. “Girl” can read as infantilizing. “Urban” carries baggage. Polysemous words—oreo, banana, fairy—have meanings we didn’t intend. Every word, in every context, requires consideration.

Adaptive difficulty

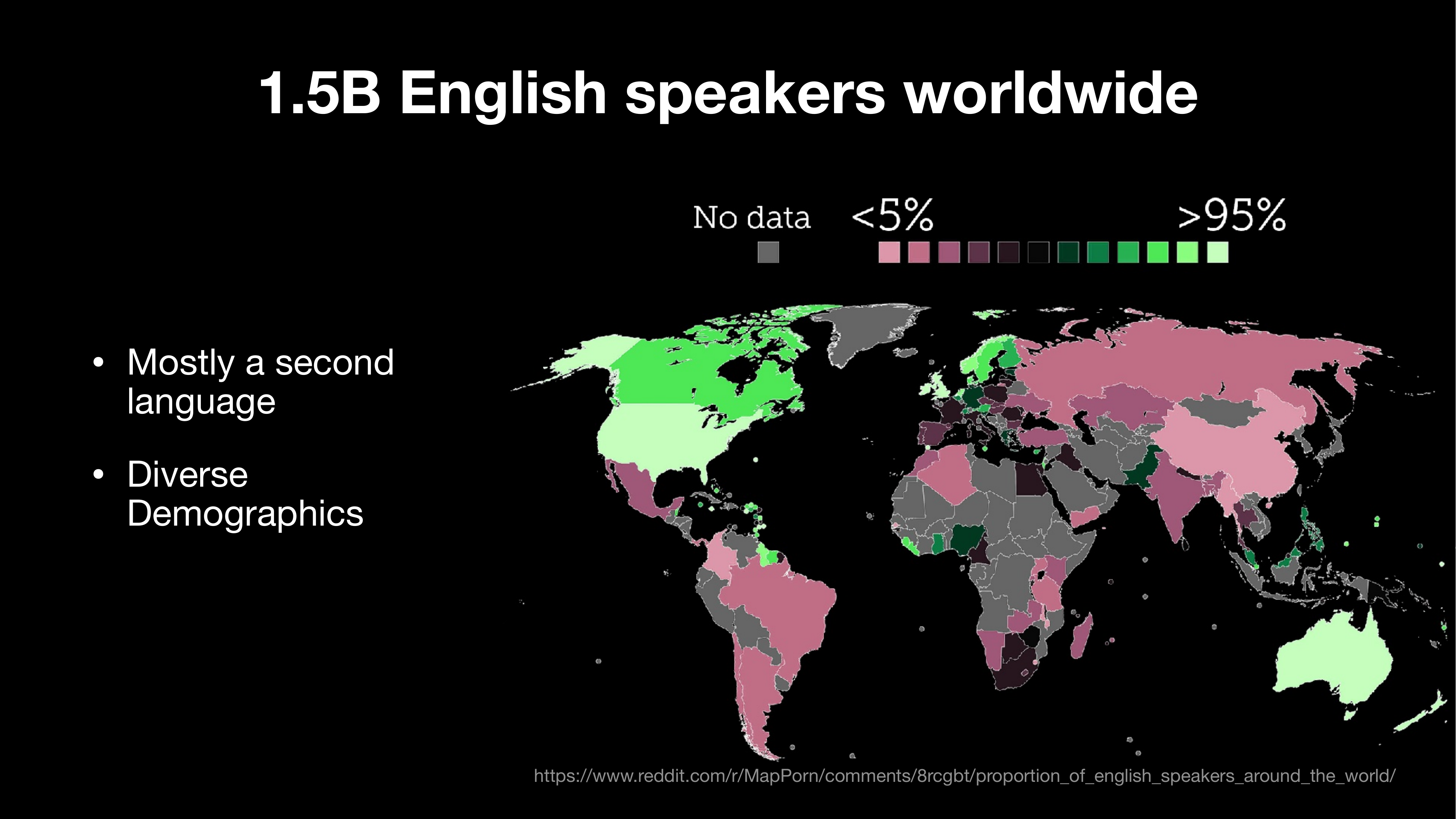

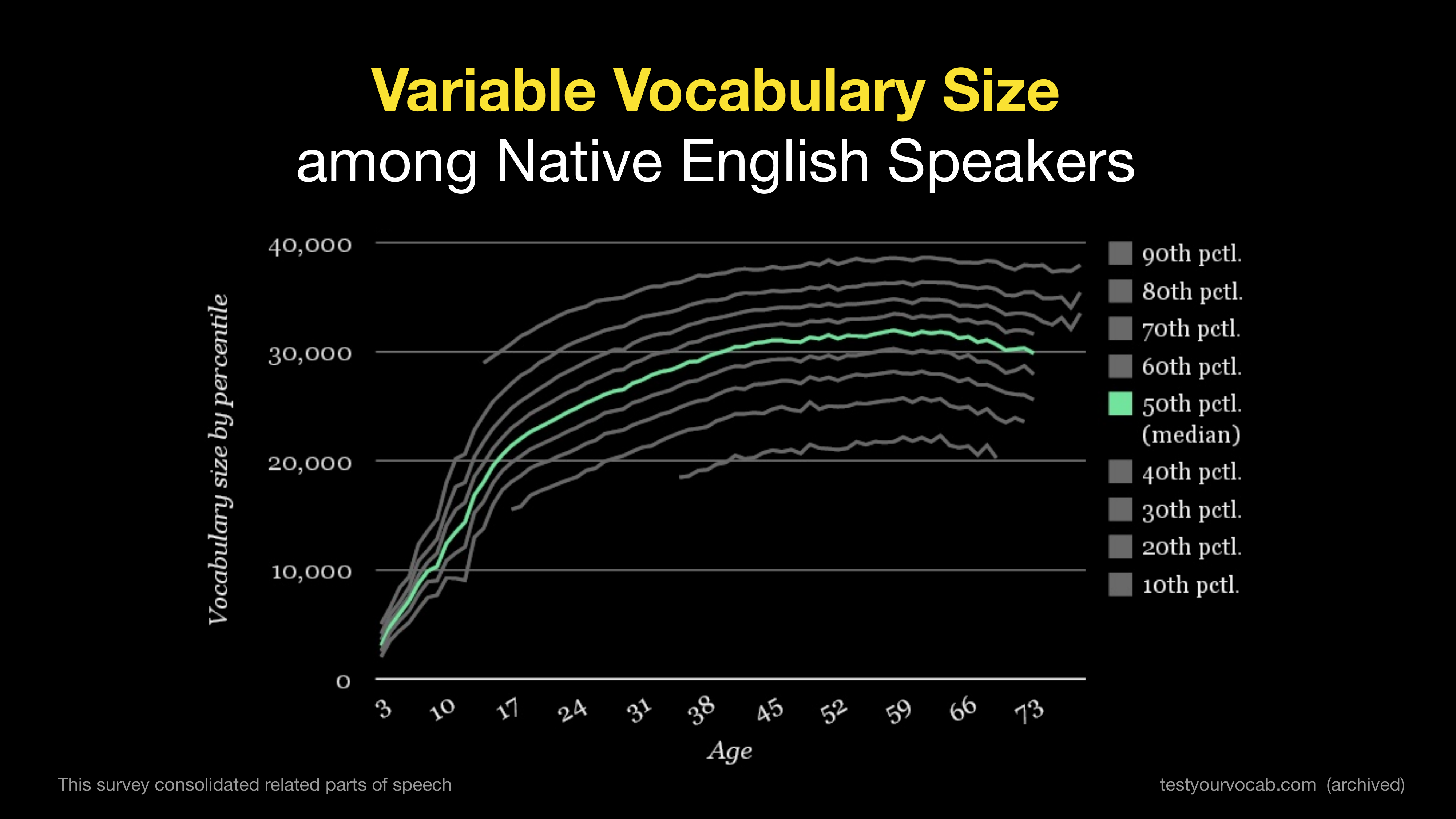

1.5 billion people speak English, and most learned it as a second language. Native speaker vocabularies range from 20,000 to 35,000+ words. Conversational non-native speakers might know 4,000. Asking players to self-assess their vocabulary level doesn’t work.

OtherWordly uses 15 difficulty levels, calibrated from multiple sources: Oxford CEFR standards, academic word lists, word frequency data from books and Wikipedia, conjugation patterns, anonymized player behavior, and AI classification. The goal is that players at any level know 80-100% of the words on screen. Word nerds aren’t bored. English learners aren’t overwhelmed.

Accessibility as design

Features we built for visual interest turned out to serve neurodiverse players in ways we didn’t anticipate. Adjustable letter visibility helps players who struggle with visual processing. Multiple difficulty levels accommodate cognitive differences. One-finger play works for players with motor impairments. Kid Mode, originally for vocabulary filtering, helps players who need simpler language.

We added explicit accessibility features: colorblind modes, dyslexia-friendly fonts, popup definitions, adjustable timing. But the core insight is that meaning-based games have accessibility advantages baked in. When there are many paths to victory, players find routes that work for their abilities.

The tension

Building semantic games requires two things that pull against each other: scale and care.

‹

›

100M relationships

AI-assisted

Decade of NLP

Every cluster reviewed

Human judgment

Cultural sensitivity

Scale: 1.5 million words, 100 million relationships. Impossible to curate by hand. AI-assisted, computationally intensive, built on a decade of NLP research.

Care: every word in context, every cluster reviewed, every cultural implication considered. Human judgment at every step. Over-eager inclusivity can offend. Careless groupings can exclude.

The technical challenge is real—we used 2.3 million supercomputer hours building the foundational data. But the ethical challenge is harder. Spelling games don’t have to worry about whether their letter tiles are culturally appropriate. We do.

We think it’s worth it. Word games can be about meaning. When they are, they can be more inclusive, more accessible, and—maybe—more impactful. We’re still learning how.

Play the Games

In Other Words — Daily pathfinding puzzle. A million paths to victory. Free on iOS.

OtherWordly — Physics-based word game in space. Coming to iOS.