There are gender wars, and then there are casualties. It wasn’t until 2011 that the behemoth toymaker LEGO acknowledged girls’ desire to build with bricks, even though the company had long before made a seemingly effortless pivot to co-branding, video games, and major motion pictures. So it’s little wonder that girls face all-too-real obstacles when […]

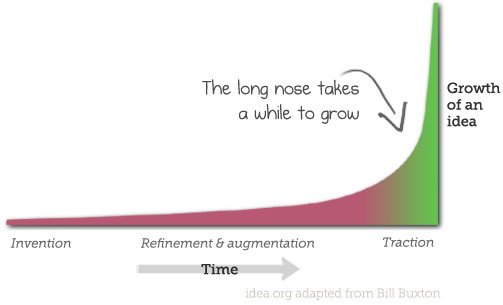

Read more Innovation takes years, if not decades. An essay by Bill Buxton, principal scientist at Microsoft Research, introduced the idea of the “The Long Nose of Innovation.” In his Jan 2008 Business Week article, he draws parallels to the ‘long tail’ of products. This has applications to all kinds of planning.

Innovation takes years, if not decades. An essay by Bill Buxton, principal scientist at Microsoft Research, introduced the idea of the “The Long Nose of Innovation.” In his Jan 2008 Business Week article, he draws parallels to the ‘long tail’ of products. This has applications to all kinds of planning.

This is what the long nose looks like as a graph (it’s a nose pointing to the left):

Innovation is not about alchemy

Buxton emphasizes that “innovation is not about invention.” He says:

An idea may well start with an invention, but the bulk of the work and creativity is in that idea’s augmentation and refinement. The newer the idea, the coarser the granularity of most analysis, and the more likely people are to say, “oh, that’s just like X” or “that’s been done before,” without any appreciation for how much work and innovation is involved in taking an idea from concept to wide practice.

This matters because educational organizations and developers may have unrealistic expectations:

Too often, universities try to contain the results of research in the hope of commercially exploiting the resulting intellectual property. Politicians believe that setting up tech-transfer incubators around universities will bring significant economic gains in the short or mid-term. It could happen. So could winning the lottery. I just wouldn’t count on it. Instead, perhaps we might focus on developing a more balanced approach to innovation—one where at least as much investment and prestige is accorded to those who focus on the process of refinement and augmentation as to those who came up with the initial creation.

Implications

- Plan for a long implementation phase. Expect there will be a long process of refinement from the initial idea until it gets a foothold. It’s this refinement and implementation stage which American inventor Thomas Alva Edison meant when he said, “Genius is one per cent inspiration, ninety-nine per cent perspiration” in 1902.

- Try to shorten the long nose. Buxton says the long nose is common, and “those who can shorten the nose by 10% to 20% make at least as great a contribution as those who had the initial idea.”

- Don’t let the turkeys get you down. Ideas which are interesting are easily dismissed by the establishment.

- Secrecy is overrated. The best ideas take years to implement. The devil is in the details, and endless cycles of refinement, testing with target audiences, promotion, and building communities/ecosystems are all key to the puzzle. This is why nondisclosure agreements are often pointless. (See classic ‘The cult of the NDA‘ and ‘Five reasons to drop NDAs‘.)

We have seen this phenomenon of a long time from a great initial concept (e.g., tablets in Star Trek in the 1960s) to broad use with the recent explosion of the Apple iPad tablet. The first table from Apple was the Newton in 1991, which took two decades of refinement to become the widely appealing product we see today.

We have seen this phenomenon of a long time from a great initial concept (e.g., tablets in Star Trek in the 1960s) to broad use with the recent explosion of the Apple iPad tablet. The first table from Apple was the Newton in 1991, which took two decades of refinement to become the widely appealing product we see today.

For an older, classic example, Buxton talks about the mouse, which started at PARC where he used to work.

First built around 1965, the mouse was first used for music and animation in 1968 by National Research Council of Canada, and around 1973, Xerox PARC adopted the mouse as the graphical input device for the Alto computer. In 1980, 3 Rivers Systems released the first commercial workstation that used a mouse, followed a year later by a Xerox workstation, and in January 1984, the first Macintosh. It was the Macintosh that brought the mouse to the attention of the general public. Still, it was not until 1995, with the release of Windows 95, that the mouse became ubiquitous. Buxton continues, “On the surface it might appear that the benefits of the mouse were obvious—and therefore it’s surprising it took 30 years to go from first demonstration to mainstream. But this 30-year gestation period turns out to be more typical than surprising.”

The idea of refinement is built into the word ‘innovation.’ Older usages from the 16th century focus on altering something already established, though common usage typically means making something new. (See OED definitions.)

Buxton says, “our collective glorification of and fascination with so-called invention—coupled with a lack of focus on the processes of prospecting, mining, refining, and adding value to ideas—says to me that the message is simply not having an effect on how we approach things in our academies, governments, or businesses.”

26 Sep 2012, 6:28 pm

[…] Innovation matters. So does refinement & augmentation: Long nose Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. Categories reading, […]